The Old Timer Part 21: Hi-lo Circuit Solves Cushion Problem

The Old Timer of Royal Oak, Mich., was a regular contributor to H&P years before we ever even heard of the internet. But most of his advice is just as useful — and interesting — today.

So rather than leave his wisdom printed on pages archived in our storage room, I pulled out issues from the late 1980s and early 1990s and have been reproducing relevant entries in this blog. Here is my 21st entry, which was originally published in the September 1989 issue:

Hi-lo circuit solves cushion problem

When specified correctly, cylinder cushions do their job of protecting a cylinder and its load against damaging impact at the end of a stroke. However, if the external application changes — say, by increasing the load, the speed, or both — the original cushions may not be able to perform acceptably under the new conditions.

We considered external shock absorbers, but the cost of rebuilding the framework was prohibitive. We investigated big rotary cams and deceleration valves, but there was no room to install them.

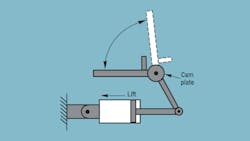

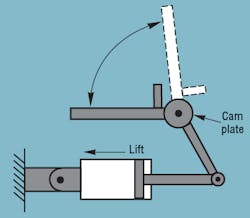

However, there was a thin rotary cam plate at the pivot point that was used to trip some limit switches, and someone remembered reading about electronically operated flow controls. Maybe we could add other limit switches to sequence high and low voltages to such a flow control.

As we suspected, the electronic valves were expensive, and we had a battle to get our hands on a single unit to try to prove our point. We installed the flow control in the tank line and ran the cylinder at full speed for 80% of its stroke; then we ramped down via the meter-out flow control over the last 20% until the cushion could handle the final stop.

The setup worked like a charm, and adjusting speed with a twist of a potentiometer was a pleasure. Too much of a pleasure, as it turned out. We had half the guys in the shop coming over to play with the new controls — zooming up and zooming down — until we caught a couple of them plotting an attempt to launch one of the wheels across the aisle. The pot wound up in a locked box with a shatterproof glass cover, so all could see the settings but not change them.

After this first success, it was easy to get and install electronic flow control valves on the other stations. Four years later, we still haven’t lost a valve—or another cylinder.

About the Author

Alan Hitchcox Blog

Editor in Chief

Alan joined Hydraulics & Pneumatics in 1987 with experience as a technical magazine editor and in industrial sales. He graduated with a BS in engineering technology from Franklin University and has also worked as a mechanic and service coordinator. He has taken technical courses in fluid power and electronic and digital control at the Milwaukee School of Engineering and the University of Wisconsin and has served on numerous industry committees.

Leaders relevant to this article: