The Old Timer of Royal Oak, Mich., Part 1

When I began my career with H&P more than 25 years ago, a regular contributor to the magazine was The Old Timer from Royal Oak. This gentleman submitted regular contributions for about five years.

The Old Timer always wanted to be kept anonymous because he wrote about situations his employer might've had problems with. I still don't know who the Old Timer was. His contributions were edited by then-editor Dick Schneider, but, after 25 years, he doesn't remember.

But we can still learn from and be entertained by the Old Timer's lessons, so I'll be reproducing most of them in the coming weeks in this blog. Here is my first entry, which was originally published in the October 1986 issue of Hydraulics & Pneumatics:

Anatomy of a weekend rush job

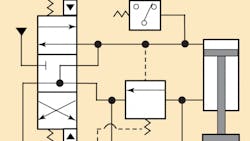

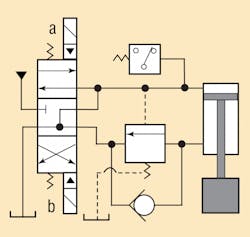

The circuit diagram and the command came down to engineering from the Ivory Tower on Friday afternoon:

“Put together a hydraulic system to run this press. It must be ready to go at 8 AM Monday or our company will down the drain. Do it any way you can — but no overtime for the engineers.”

On the positive side, the press already had a cylinder; there was a pump system we could tap into; pipe, fittings, and hardware were in stock; and maintenance people were scheduled to work over the weekend anyhow. All we needed was a 4-way valve, a pressure switch, and a counterbalance valve — just three simple components. On the negative side, it was too late to order anything from outside and get it delivered, so we had to find these components in our own shop. Time to get on the phone.

We found one unit that had several rebuilt 4-way valves. We could have one but they were without bases. Another unit had some bases and would trade for one. Pressure switches were in Central Stores, and our own department’s secret cache of surplus components included a couple of counterbalance valves. One of them probably would work.

So all we had to do was copy the sketch and issue instructions to our weekend people:

·get rebuilt 4-way valve from Unit A

·get subbase from Unit B

·requisition pressure switch from Central Stores

·clean up one of these counterbalance valves, and

·pipe up the system per the diagram.

My home phone rang at 2 AM Monday. “Better get down here. The press won’t work.”

At the plant we verified that this report was correct. Energizing either solenoid produced no reaction. We knew the valve had been completely rebuilt. Could the sub-base be the problem? A little checking revealed that the old style valve had an external pilot and an external drain. The newer sub-base was set up for internal pilot and internal drain. Did we want to experiment with changing the plugs around? No, it was easier to scavenge another valve from one of the machines on that new production line that wasn’t scheduled to start up for two weeks.

With he new valve installed, something finally happened when we energized a solenoid — we got an oil shower. Some of the bolts used to mount the valve were a fraction too long and bottomed out before they squeezed the O-rings. Time out to grind down the bolt ends.

With everything reassembled we tried solenoid a. The press started down, then stopped, sat there, started again, stopped again. We knew we had plenty of pump flow, so it was time to examine the counterbalance valve. We changed the external pilot to an internal pilot on the incoming side and wound the spring down considerably. Now the press came down smoothly and quickly — but it wouldn’t go back up.

A closer look at the counterbalance valve revealed that it had no bypass check valve passage. (Where did that old dog of a valve ever come from?) Three aisles over, another press was being rebuilt. We borrowed a true counterbalance valve from that machine. After we installed that valve, the press cycled properly, but the pressure switch worked erratically.

Checking make and model number, we learned that Central Stores had unloaded an ancient obsolete model on us. The box was wet and the switch was rusty — clues that it had been stored near a roof leak. One of our guys remembered seeing some new switches in incoming stock. All we had to do was pop a lock and climb a fence to acquire one.

The tooling guys moved in for their work, and when they were done, the press was ready to start production — except that after 15 minutes, the press slowed down, then stopped. We thought everything was okay on our end, so maybe there was bearing and guide misalignment.

After a call to the mechanical guys and another 15 minutes of shimming and alignment, the press started up and ran fine — but only for another 10 minutes. The mechanical guys said they couldn’t do anything more so we went back over the hydraulic side again.

One of the piping guys recalled that he had to turn a cap around on the counterbalance valve to pipe the drain. We got out the book on the valve and studied it. Sure enough, it was a model that had a multiple-position head: one position for internal pilot, another for external drain, another for internal drain, etc. The head on our valve had been turned to a blank spot, so there was no drain. After 10 or 15 minutes of operation, enough leakage built up in the spring chamber to create a hydraulic lock, and the counterbalance couldn’t open.

With the head turned around to the correct position, the press ran beautifully for the next three years until a model change eliminated the operation. On that early Monday morning we had violated a slew of company regulations and broken a couple of union rules — but we were in production, and management was happy. However, I still shudder to think what might have happened if the project required more than those three simple components.

About the Author

Alan Hitchcox Blog

Editor in Chief

Alan joined Hydraulics & Pneumatics in 1987 with experience as a technical magazine editor and in industrial sales. He graduated with a BS in engineering technology from Franklin University and has also worked as a mechanic and service coordinator. He has taken technical courses in fluid power and electronic and digital control at the Milwaukee School of Engineering and the University of Wisconsin and has served on numerous industry committees.