How to Protect Hydraulic Swivels from Hostile Environments

Regardless of the industry or application, hydraulic system contaminants can make a big mess, and in more ways than one. Challenges from contamination can lead to out-of-service equipment and seal failures to replacement needs, all affecting productivity. Contaminants, such as water, dust, dirt, and metal, will vary from industry and application, but the most common hydraulic challenge associated with contaminants is seal failure. Extreme temperatures can also cause damage to the hydraulic system if not properly addressed.

Contaminants in Hydraulic Swivels

Hydraulic swivels are similar to hydraulic cylinders in terms of the contaminants they are exposed to. The main difference lies in how each operates. Cylinders must contain fluid and exclude contaminants against linear motion, whereas swivels seal against rotary motion. When a cylinder’s piston rod is exposed to debris, a rod scraper is designed to remove the debris before it reaches the main rod seal. Because of its rotational motion, a hydraulic swivel does not have the luxury of a scraper. Therefore, swivels should be designed to keep debris away from seal areas.

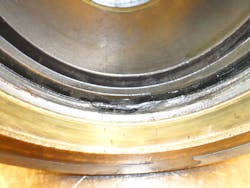

Contamination caused a large ring around this ductile-iron spool to be eaten away. Rather than galling, the ductile iron broke apart.

Arguably, the most common form of contamination is dirt. Dirt, however, is not necessarily the most dangerous contaminant. Dirt typically ingresses slowly into the swivel as more dirt accumulates at the area where the spool and housing meet. The dirt can start to grind away at the outward facing lip of the excluder seal. If dirt gets underneath the lip, it can also cause damage to the surface of the metal, further degrading the ability to seal out the dirt. Dirt can also sneak its way around the outside of some types of excluder seals.

Water is another common contaminant. Water ingression can happen at any point in the hydraulic system, but it occurs most often at the sealing surfaces of mobbing components. Because they often are located deep within a machine’s structure, hydraulic swivels often are more isolated from dirty environments than cylinders are. Although water itself does not cause the wear and damage of abrasive contaminants, water can cause rust, which can become abrasive debris within the hydraulic system. Water also degrades an oil’s ability to lubricate.

Metal particles can be either from external or internal sources. External metal debris cause damage like dirt. However, metal particles can be even more abrasive and can easily cut seals. Metal particles tend to be larger than dirt particles and have a harder time entering cavities that house hydraulic seals.

Internal metal particles can be caused from hydraulic components that are not properly cleaned or deburred. This type of debris can be very damaging, not only by cutting seals, but also by causing galling if the particles get into the extrusion gap between the spool and housing. When a metal particle starts the galling process, the small bit of metal debris turns into a large ball that fuses the spool and housing together. This can cause catastrophic failure by locking up the swivel. This happens more often in swivels with mild steel spools and housings. When a mix of materials is used, such as mild steel and ductile iron, the ductile iron will usually disintegrate before it fuses together.

Contamination caused severe damage to this AISI 1026 carbon steel housing. Rather than break away, mild steel will act gummy and ball up, creating a large impedance to rotation. If this had been mated with a mild-steel spool, the two would have fused together and prevented rotation.

Offshore swivels exposed to salt water should be constructed of corrosion-resistant materials, such as SAE 316 stainless steel. Additional sealing is required to keep the salt water out of the swivel–e.g., multiple outward facing U-cups with grease traps. Salt water can be more damaging to other parts of the hydraulic system than the swivel itself if it gets into to the system.

How to Minimize Damage

Minimizing damage from external contamination requires keeping debris away from sensitive areas. Internal contamination can only be addressed during the manufacturing and assembly process. One OEM found chips from the manifold machining process that became stuck in the valves and pieces of casting in the hydraulic system. As the OEM explained, “Contamination in hydraulics can create warranty costs for us if the system fails in the warranty timeframe and from contamination that wasn’t introduced while in the field.”

Keeping debris out and pressurized oil in is the goal of hydraulic seals. When the seals don’t make clean, consistent contact with the mating surfaces, debris can be introduced, and oil can escape. Debris must be kept far away from the swivel to keep the sealing contact area clean and smooth. Within the swivel, outward facing excluder seals deflect debris away from sensitive areas such as the seals. UEA uses large O-rings and V-ring seals as additional barriers for debris ingress.

Damage From Extreme Temperatures

Extreme temperatures bring their own set of challenges. Elastomeric seals have a temperature range for effective operation, but operation above or below this range will reduce performance of the seals. This can cause anything from a small leak to complete seal failure.

Extremely high oil temperatures (above 230°F) can start to degrade many different types of seals. The elastomers used as energizers for the U-cups and cap seals will start to harden and take a set, reducing the elastic properties of the energizers. Once the energizers have taken a set, they become less effective in sealing. It becomes more apparent that the energizers have been overheated when they are then exposed to cold temperatures or side loading, both conditions that are outside the optimal environment for sealing.

Extreme cold (−40° F) can also affect how well the seal performs. Unlike excessive heat, cold temperatures usually don’t create lasting damage to the seal. In cold temperatures, the seal typically becomes hard and rigid, tending to allow oil to leak past. The swivel will seal up better as the oil temperature increases. Softer seals tend to perform better at low temperatures; however, a softer seal will have more difficulty being effective at high temperatures and high pressures. It is a tradeoff between the two extremes.

Brady Haugo is hydraulic engineering supervisor at United Equipment Accessories Inc., Waverly, Iowa.

About the Author

Brady Haugo

Hydraulic Engineering Supervisor

Leaders relevant to this article: